Strengthen Working Family Tax Credits to Reduce Poverty and Expand Opportunity

Chuck Marr

July 24, 2019

Many people across the country have stories about how a little-known part of the tax code—the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit—helped support their families and get ahead.

“As a single mother and new graduate, I count on the Child Tax Credit tremendously,” Travis from Tennessee told the national advocacy organization MomsRising. “I am typically in the category of the ‘working poor,’ meaning I don’t make enough money to live above the poverty line, but I don’t qualify for state aid. This makes it extremely hard to afford anything other than our base line bills and groceries for the month. If something goes wrong with my car or an appliance in my house, it causes me panic attacks because I don’t [know] where I’ll get the money from. . . . [T]he Earned Income Tax Credit also provides my daughter and I with funds that allow me to pay for opportunities for her that would otherwise be unavailable.”

Many low-income working families like Travis’s struggle to get by, as their costs have risen faster than their wages over the last several decades. Policymakers can help by strengthening the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC). These two highly successful federal tax credits lift millions of people out of poverty and give working people and children a better shot to get ahead, both now and over the long term.

Improving the EITC and Child Tax Credit — through changes like those in the Working Families Tax Relief Act, recently introduced in the Senate — should be a key part of an agenda to reduce income inequality and boost working people’s wages.

Improving the EITC and Child Tax Credit — through changes like those in the Working Families Tax Relief Act, recently introduced in the Senate — should be a key part of an agenda to reduce income inequality and boost working people’s wages.

The EITC, enacted under the Ford administration in 1975, has long enjoyed bipartisan support. President Reagan called the 1986 tax reform bill, which substantially expanded the credit, “the best anti-poverty, the best pro-family, the best job creation measure to come out of Congress.” President Clinton signed another major EITC expansion in 1993, while Presidents Bush and Obama enacted improvements as well.

Working people receive the EITC starting with their first dollar of earned income; the credit grows with their earnings until reaching a maximum level and then phases out at higher income levels. The EITC offsets federal payroll and income taxes and boosts the incomes of people who work hard but earn little. Families across the United States use EITC refunds to pay for necessities, repair homes, maintain vehicles they need to get to work, or get additional education or training to boost their employability and earning power.

Stephanie in Missouri, for example, explains: “I am a single working mom of four. My income is low, but I’m proud to support my family, running my own business from home which allows me to be here for my kids. Without the EITC my income would not be enough to cover our basic necessities, like food, housing and utilities.”

Stephanie in Missouri, for example, explains: “I am a single working mom of four. My income is low, but I’m proud to support my family, running my own business from home which allows me to be here for my kids. Without the EITC my income would not be enough to cover our basic necessities, like food, housing and utilities.”

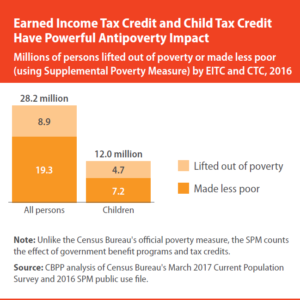

The extra money that people get from the EITC also helps them achieve more financial stability. The EITC lifted about 5.8 million people out of poverty in 2016, including about 3 million children.

The Child Tax Credit, enacted in 1997 and expanded with bipartisan support since 2001, helps working families offset the cost of raising children. It’s worth up to $2,000 per child under age 17 and is partially available to low wage working parents.

The CTC lifted roughly 2.8 million people out of poverty in 2017, including about 1.6 million children, and lessened poverty for another 13.1 million people, including 6.7 million children.

Congress Can Improve the EITC and Child Tax Credit

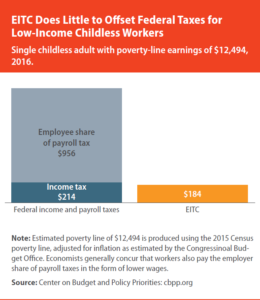

Despite their success, both the EITC and the Child Tax Credit have shortcomings that policymakers should address in order to target more assistance to those who need it most. The EITC for working people not raising children in the home is extremely small — too small even to fully offset federal taxes for workers at the poverty line. A childless adult earning poverty-level wages of $13,340 as a cashier, for example, owes $1,135 in federal income and payroll taxes and receives an EITC of just $172. As a result, this person is one of the over 5 million low-wage childless working people whom the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty.

Despite their success, both the EITC and the Child Tax Credit have shortcomings that policymakers should address in order to target more assistance to those who need it most. The EITC for working people not raising children in the home is extremely small — too small even to fully offset federal taxes for workers at the poverty line. A childless adult earning poverty-level wages of $13,340 as a cashier, for example, owes $1,135 in federal income and payroll taxes and receives an EITC of just $172. As a result, this person is one of the over 5 million low-wage childless working people whom the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty.

Beyond a threshold of $2,500 of earnings, the Child Tax Credit amounts to 15 cents on each additional dollar earned. This means the poorest children qualify for a very small credit or none at all, even though they are the children who need it most and for whom it would have the largest impact.

Unfortunately, when policymakers made major changes to the tax code most recently in 2017, they largely ignored the opportunity to raise living standards for low- and moderate-income people. The 2017 tax law was heavily tilted toward the wealthiest households and profitable corporations instead of working families. And even its highly touted increase in the CTC provided zero or only a token amount (ranging from $1 to $75) to 11 million children in low-income working families because their incomes were too low.

A landmark bill in Congress offers a promising path forward. The Working Families Tax Relief Act, introduced in the Senate by Senators Sherrod Brown, Michael Bennet, Richard Durbin, and Ron Wyden with more than 40 co-sponsors, would significantly strengthen the EITC and CTC. These expansions would make 46 million households more financially secure and benefit 114 million people — including 49 million children. Families of all races would benefit, including 24 million white families, 9 million Latino families, 8 million Black families, and 2 million Asian American families.

The bill would build on the EITC’s success among families with children, boosting their credit by roughly 25%. And it would substantially improve the credit for low-wage working people without children at home. It would raise their maximum credit (from roughly $530 to $2,100), raise the income limit to qualify for the credit (from about $16,000 for a single individual to about $25,000), and expand the age range of workers eligible for the credit (from 25-64 to 19-67). The above-mentioned cashier would see her EITC rise from $172 to $1,797, lifting her $662 above the poverty line.

The bill would also make big improvements in the Child Tax Credit. As discussed above, the current credit partly or entirely leaves out many poor families with children because they earn to little. The bill would make the CTC available to all poor families – and not dependent on earnings — and expand the credit for children under age 6. Almost all low- and middle-income families with children would receive a $2,000 Child Tax Credit for each child age 6 or older and $3,000 per child under 6.

The larger tax credit for young children would help respond to the special economic challenges that families with young children can face. Parents in these families tend to have lower wages because they are often less advanced in their careers, and the high cost of child care for young children can force many parents to choose between paying that expense or getting by on just one income.

To better target the Child Tax Credit to families who need it most, the bill would also begin phasing the credit down for married couples with incomes over $200,000 (compared to $400,000 under current law) and single parents with incomes over $150,000 (compared to $200,000).

Putting its EITC and CTC expansions together, the bill would make a substantial difference for low- and moderate-income working families. A single mother of two earning $20,000 would get a $3,700 increase, for example, while a married couple with two young kids making $45,000 would get a $3,500 increase. The bill would cut child poverty by 28%, lifting 3.1 million children out of poverty and making another 7.7 million children less poor.

Putting its EITC and CTC expansions together, the bill would make a substantial difference for low- and moderate-income working families. A single mother of two earning $20,000 would get a $3,700 increase, for example, while a married couple with two young kids making $45,000 would get a $3,500 increase. The bill would cut child poverty by 28%, lifting 3.1 million children out of poverty and making another 7.7 million children less poor.

The bill would also have lasting benefits for children, helping not only them but our country as a whole. Studies show that kids in low-income families that receive added income from working-family tax credits like the EITC and Child Tax Credit do better in school and are likelier to attend college. They also are likelier to earn more as adults due to their higher skills and more years of education. And, kids whose families receive working-family tax credits are likelier to avoid the early onset of illnesses associated with child poverty, further boosting their earnings ability.

“Both the EITC and Child Tax Credit have made a huge difference for our family and have been critically important to our financial stability as parents of young children,” Kathleen from Utah explains.

That’s a key message for policymakers as they debate ways to reduce inequality and restructure the 2017 tax law to expand opportunity for low-wage working families. Strengthening the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit would advance both of those goals.

Chuck Marr is the Director of Federal Tax Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). CBPP is a nonpartisan research and policy institute founded in 1981 to analyze federal budget priorities, with a particular focus on how budget choices affect low-income Americans. CBPP pursues both federal and state policies designed to reduce poverty and inequality and to restore fiscal responsibility in equitable and effective ways. Learn more at www.cbpp.org.

Special thanks to MomsRising for sharing the stories from people and families across the country who receive the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit.

This story was originally published in the July 2019 issue of Connection magazine. Read the full issue.