Faces of our Spirit-Filled Network: Fr. Terry Moran

Fr. Terry Moran

July 10, 2018

Tell us a little about yourself and the work you do.

I am a Catholic priest, an associate of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Peace, and currently minister as the Director of the Office of Peace, Justice, and Ecological Integrity for the Sisters of Charity of Saint Elizabeth, a congregation of women religious, mostly in New Jersey, with some sisters in other states and in Haiti and El Salvador.

How did you first learn about NETWORK and what inspired you to get involved?

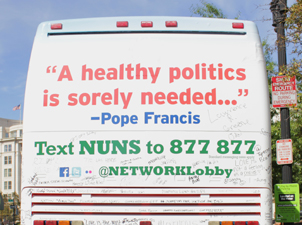

I remember when NETWORK was founded and the excitement it generated in sisters who were friends of mine. NETWORK incarnated what we were talking about in theology after Vatican II – that the gospel compelled us to become involved in the political process, to build on our history of direct service by engaging in structural change.

What issue area are you most passionate about?

Climate change and learning how to foster a healthier human/Earth relationship is my greatest passion. Any other social issue is contingent on us facing the climate crisis. There can be no just human society on a dying planet.

How are you engaging your community on important social justice issues?

In as many ways as possible: I send out regular action alerts on issues that are important to us; a monthly e-newsletter called JustLove; two ecospirituality groups that meet monthly; regular workshops and talks; a Facebook page; recently I distributed a refrigerator magnet with a graphic of our Justice, Peace and the Integrity of Creation (JPIC) priority issues so that the sisters think about them as they get their morning orange juice.

How has your advocacy for social justice shaped your view of the world?

I come from a family in which political engagement was an important value so there’s a restlessness in my genes for a world that is more just, peaceful, and verdant.

How does your faith inspire you to work for justice?

My religious formation was in the early post-Vatican II days when “a faith that does justice” was shaking our sleepy 1950’s Catholicism. I’m very happy that Pope Francis is putting the social agenda of the gospel front and center again. I think his encyclical Laudato Si’ is the most compelling program available today for where the world needs to go.

Who is your role model?

Two people that are daily inspirations for me: Margaret Anna Cusack, the founder of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Peace –the community of which I’m an associate. She was a 19th century Irish social justice advocate and prolific writer who drove bishops crazy. Her book Women’s Work in Modern Society (1875) was among the first to explore the role of women in economic life. I love her quote, “People make a lot of the sufferings of the Desert Fathers but they were nothing compared to the sufferings of the mothers of the 19th century.”

Another is Daniel Berrigan, SJ, who has been a mentor for me since I first met him on his release from prison in my hometown, Danbury, CT in 1972. His contemplative searching of the scriptures that led to a life of resistance to war has been a life-long model for me.

Right now, I am most inspired by my seven friends of the Kings Bay Plowshares action who entered the largest Trident submarine base in the world on April 4, 2018 and enacted the prophecy of Isaiah 2 by hammering and pouring blood on these instruments of mass destruction. I have their photo on my desk and often turn to it in the course of the day in gratitude and prayer. Their willingness to put their own lives and plans on hold and to risk prison for the sake of the gospel of non-violent resistance is tremendously inspiring to me.

Is there a quote that motivates or nourishes you that you would like to share?

“The world is violent and mercurial–it will have its way with you. We are saved only by love–love for each other and the love that we pour into the art we feel compelled to share: being a parent; being a writer; being a painter; being a friend. We live in a perpetually burning building, and what we must save from it, all the time, is love.”– Tennessee Williams

What social movement has inspired you?

Growing up in the 60’s, I’ve been deeply formed by my involvement in the peace movement and the women’s movement. I remember participating in the first Earth Day in 1970. Most recently I’m very inspired by Black Lives Matter, the leadership taken by young people against gun violence, and the work of an organization of Dreamers called Cosecha who are risking their own safety for dignity for all the undocumented.

What was your biggest accomplishment as an activist in the past year?

That I haven’t lost my mind and have been able to keep going in the vile political climate in which we live.

What are you looking forward to working on in the coming months?

Starting an organic garden on our motherhouse property. There is something healing about getting your hands in the dirt. Also working with a local organization to welcome a third refugee family.