After Shelby: The Need to Reinstate Crucial Voting Rights Protections

Sister Quincy Howard, OP

Updated: June 27, 2019

We at NETWORK, with many of our partners, are naming this week “Shelby Week” in recognition of the six years that have passed since the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder.

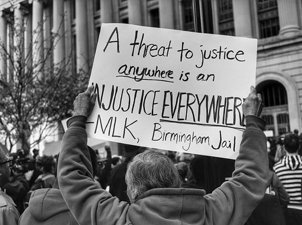

In the aftermath of the June 25, 2013 Shelby decision – which gutted key protections of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) – states and localities across the country jumped to enact restrictive voting laws, disenfranchising millions of American voters. For six years, civil rights organizations have been fighting back against these discriminatory laws. We need Congress to restore the VRA to its full strength to ensure that all eligible voters have equal access to the ballot and that every vote counts.

The ideal of “one person, one vote” is central to our understanding of democracy in the United States, but the reality in our country falls short. While the legal discrimination that prevented people of color from voting for hundreds of years is no longer in place, today a new combination of restrictive standards and requirements keep voters from exercising their right to vote. Whether implementing voter ID requirements, purging voter rolls, restricting early voting, or closing polling locations, state-level election laws can make it considerably harder, if not impossible for many eligible citizens to vote. Furthermore, these requirements have a disproportionate impact, often by design, on low-income and voters of color who are less likely to have flexible schedules, access to transportation, or a government photo ID.

Many of these tactics are familiar to communities of color, but ever since the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 there had been an effective mechanism in place to apply federal oversight of potential voting rights violations. Specifically, Sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) used a formula determined by the VRA in 1965 to identify jurisdictions with histories of racial discrimination and subject them to federal preclearance requirements prior to implementing any changes in voter registration or casting of ballots. In 2013, however, the Shelby County v. Holder Supreme Court decision stripped the VRA of this preclearance mechanism—deeming the formula outdated—and opened the door for states to pass more restrictive voting standards with impunity.

Since the Shelby ruling, 23 states have freely implemented more restrictive voting laws and conducted elections accordingly. The only recourse left is under Section 2 of the VRA—to challenge these laws after the fact. Meanwhile, the resulting voter disenfranchisement has already taken place and the results of potentially rigged elections stand. Accordingly, unfair elections around the nation have begun to resemble a discriminatory game of wack-a-mole: lawsuits of voter discrimination have quadrupled in the five years since the Shelby decision. Expensive and slow-moving litigation is an untenable approach to reinstating fair elections; and Section 2 offers no remedy for the impacts of disenfranchisement.

In contrast, under the Section 5 process the Justice Department provided quick, inexpensive reviews and decisions on proposed changes to voting requirements or procedures. The vast majority of proposed changes to elections were cleared and there was space to appeal decisions when they were not. It was a system that worked; the VRA without this preclearance mechanism is not working.

This Wednesday, the House Oversight and Reform Committee will be conducting a hearing on “Protecting the Right to Vote: Best and Worst Practices.” Chairman Jamie Raskin (MD-08), who is also a professor of Constitutional Law, the First Amendment, and Legislative Process, will lead the Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Subcommittee in this effort to get to the bottom of voter suppression today.

For six years, Congress has made multiple unsuccessful legislative attempts to update the preclearance formula and restore this crucial provision of the VRA. Part of the process to adopt a preclearance formula that the courts will uphold is gathering and documenting evidence of efforts to disenfranchise voters. Congress is currently building this record to demonstrate ways in which jurisdictions have changed laws to disenfranchise voters, particularly voters of color. Most recently, we can look to states like Georgia, Texas, North Carolina, North Dakota, Florida, and Alabama for flagrant examples of manipulated election procedures that effectively suppress the vote of communities of color.

Throughout April and May, the House Administration Committee’s Subcommittee on Elections is holding a series of field hearings on voting rights and election administration. Hearings have taken place in Standing Rock, ND; Halifax, NC; and in Cleveland, OH. Still to come are field hearings in Alabama and Florida to review and hear testimony about the impacts of new voting and registration laws on communities of color. These hearings are the opportunity to examine what voter disenfranchisement in the 21st Century looks like—so we can prevent it from happening.

In late February, Representative Teri Sewell (AL-07) and Senator Patrick Leahy (VT) introduced the 116th Congress’ high-priority legislative fix to restore and extend these key provisions of the VRA. It’s not the first time that a “Shelby-fix” bill has been introduced since 2013, but this year it’s coming on the heels of an historic election in which rampant and flagrant voter suppression was apparent. H.R. 1 (the For the People Act) has also already passed in the House and specifically named this as a crucial component for democracy reform.

The Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2019 (VRAA), H.R. 4, represents the most robust and inclusive proposal to revise the criteria for determining which States and political jurisdictions should be subject to preclearance requirements. Specifically, the formula proposed in VRAA subjects any jurisdiction with 15 or more voting-rights violations over the past 25 years to 10 years of federal preclearance. The threshold would be lowered to just 10 violations if any of them were committed by the state itself. VRAA is not solely a defensive measure. It’s intended to be punitive, to deter people who take advantage of the fact that there are few real consequences for officials found in violation of the Constitution. The VRAA would add teeth that the Voting Rights Act didn’t have even at full strength. While alternate bills are already emerging with less-expansive formulas, NETWORK strongly supports H.R.4 as the way to quickly address and end voting rights abuses that have become commonplace across our country.