Concern for our Common Home as Pruitt Confirmation Vote Nears

Mackenzie Harris

February 14, 2017

Pope Francis says that we are called by our faith to care for our creation – that the degradation of the environment is a sin. During this polarizing time, I think it’s safe to say that we all need to remember the significance the future of our environment has on our very own lives, and future generations to come.

The rhetoric in the past few weeks, let alone the last year, has been astonishing to say the least. Using terms like “alternative facts” about science and the environment were just another ploy to delay action on climate change for the new Administration, according to members of Congress and advocates who spoke alongside Senator Tom Carper (D-DE) at a press conference about on the Senate confirmation process for Scott Pruitt to lead the Environmental Protection Agency last week.

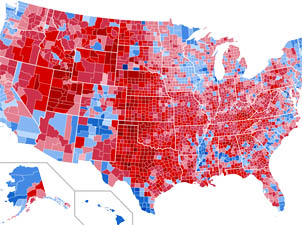

The divide amongst our parties on climate change and the role of the Environmental Protection Agency has unfortunately grown deeper in this past election with President Trump denying the existence of a connection between human activity and climate change.

Sister Simone Campbell stated during the press conference that, “This is not polarized politics; these are actual facts. And we must respond to the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.” Senator Carper, meanwhile, said there is an urgency to have the Environment Protection Agency backed by science, not opinion.

The fact that the future of the EPA could very well be in the hands of a man who has been scrutinized for his skepticism of the EPA is almost as frightening as President Trump’s failure to recognize climate change, or worse, his transition leader, Myron Ebell’s plan to cut the EPA’s workforce by two-thirds.

I know that global climate change threatens all people and all nations, and like so many other challenges to justice, global climate change disproportionately impacts people in poverty and others who are vulnerable and marginalized members of our society.

Ignoring climate change or cutting the EPA’s workforce has an effect on us all.

I fear that during this time of partisan divide we won’t hear the cry for our earth or the cry of the poor. I’m afraid that those most affected will be silenced by the deafening rhetoric of this new Administration. I hope and pray that President Trump will step back and realize what he is doing to our Mother Earth.