Building a New Vision for Our Democracy: The Importance of Voting Rights

Senator Tom Udall

April 17, 2020

This reflection is part of our 2020 Lent Guide: Becoming Spirit-Filled Voters.

This season, before an incredibly important election, we must reflect on the state of our democracy. Democracy represents more than a system of government. It is the sacred affirmation that each voice matters equally in one nation — and that a representative government must be of, by, and for the people.

But today, the American people are losing faith in our democracy. They see the evidence with their own eyes as the wealthy purchase influence in political campaigns and drown out the voices of the people. Voting rights are under assault, foreign adversaries interfere in our elections, and so-called public servants use their offices to help themselves and their friends — instead of the people they are supposed to work for.

Our voices do count. Our voices count when we vote in each election, especially this year. And they count when we organize, march, and speak out about injustice.

But there is no doubt that our democracy is in a crisis. Since coming to Congress in 1999, I’ve seen firsthand the corrosive influence that big money is having on our political system. The influx of unlimited contributions and secret donations into campaigns has fueled the hyper-partisanship we see across the nation, including in Congress.

Special interests try to dominate the political agenda, to the detriment of the common good. This has obscured the fundamental values that should define our work. Values like social justice. Feeding the hungry. Helping the poor. Making peace. And caring for our earth.

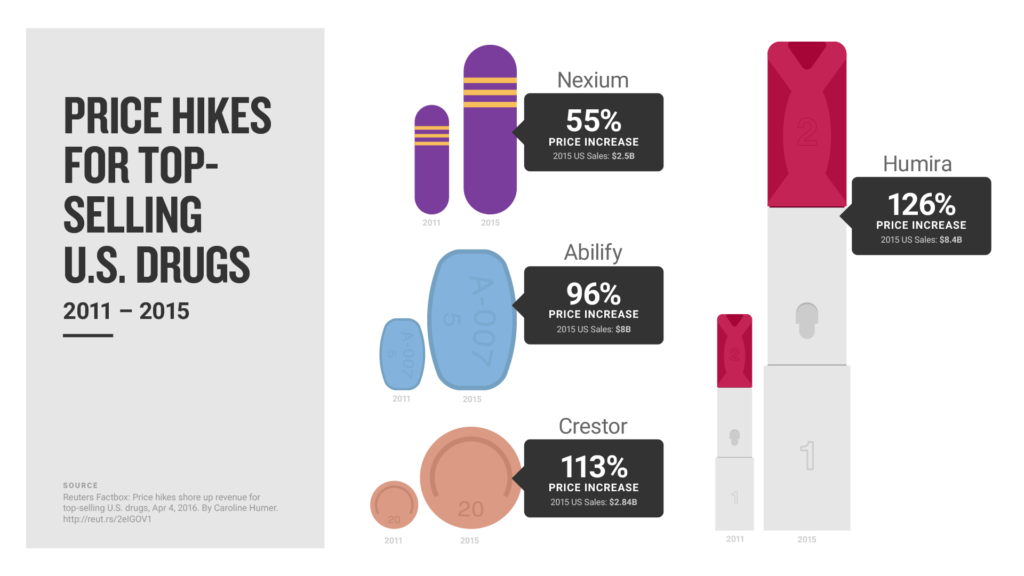

The money in our politics fuels a disconnect between what people in our democracy want and what Congress is giving them. The people want action on climate change. The people want universal, affordable health care. Economic justice and food security for families. Commonsense gun safety laws. And they demand that we welcome the stranger and treat immigrants as human beings.

These are priorities for the vast majority of Americans. And there is a direct link between Congress’s inaction on these issues and barriers to the ballot box and our broken campaign finance system.

We live in a representative democracy. But Congress is not representing the people. The 1% are heard, while the other 99% are not.

In Congress, we are fighting for reforms to make our democracy work: increasing access to the ballot box, putting an end to the influence of secret money in elections, and raising the ethical bar in government.

The For the People Act (H.R.1) makes it easier to register to vote and to cast a ballot. In a society where special interests artificially widen and sustain our divisions, it has never been more important to ensure that each and every voice is heard. H.R.1 also returns our campaign finance system to the hands of the people, shining a light on secret campaign contributions and empowering small donors.

We need to put an end to the idea that money equals speech and reign in an out-of-control campaign finance system. And the only way to do that is to exercise our most fundamental and sacred democratic right — the right to vote.

Our democracy cannot be fully realized unless we, the people, vote. We deserve a representative democracy, with elected leaders who understand our concerns and are committed to fight for all voices to be heard. For our common values. And for the future of our democracy in this election and all the elections to come.

Senator Tom Udall represents New Mexico, and is a champion of restoring voting rights to marginalized groups for a more equal and just democracy.

Senator Tom Udall represents New Mexico, and is a champion of restoring voting rights to marginalized groups for a more equal and just democracy.