The First 100 Days

Strategy & action for the 2nd Trump Administration and the 119th Congress

TAKE ACTION!

Make a visit to the district office of your Member of Congress with NETWORK materials.

How to Visit Your Representatives Local Office

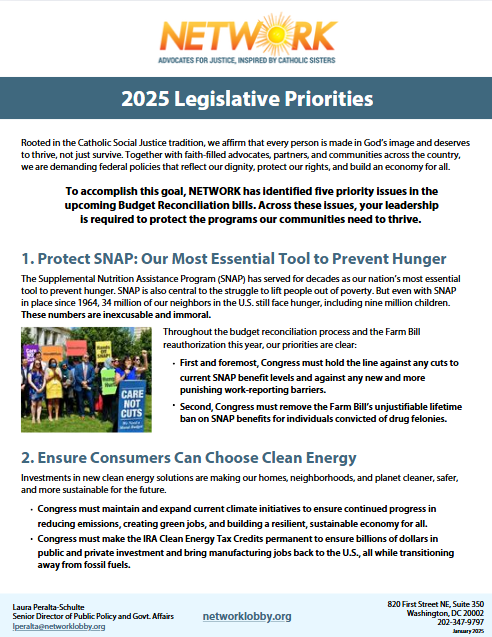

During the House January Recess (Jan. 27-31), NETWORK advocates across the country are visiting their Representatives’ in-district offices to share information about NETWORK and our 2025 Legislative Priorities. You don’t have to be a policy expert to participate. This is a quick, relationship-building activity that is focused on values. We hope you will join us!

Making the most of your visit to your Representative’s in-district office

Whether your Representative is brand-new to Congress or has been serving your district for 20 years, it’s important for you to build a relationship with the staff in their in-district offices and tell them about NETWORK and our policy priorities. In-district staff are members of your community, and getting to know them and demonstrating that you care about your district is your first step to building or strengthening your relationship with your Member of Congress.

While this visit is not a formal lobby visit, it is an effective way to introduce yourself and NETWORK to the in-district staff—and increase your chances of getting a meeting with your Representative the next time they’re home. Here are some tips for having a successful visit:

- Confirm the office’s location and hours. Depending on the size of your district, your Representative may have one or several offices, and their addresses and phone numbers will be listed on their official house.gov website. Call ahead to confirm the location and find out what days and times you can visit. If you’re going in a group, make sure that everyone knows what time you’re visiting the office.

Important Note: While we are hoping for the visits to take place during January Recess, we also recognize that newly elected officials may not have all their in- district offices set up yet. If your local office isn’t open yet, please maintain communication and visit as soon as you’re able. It’s crucial for new Members of Congress to meet you and learn about NETWORK!

- Connect with other local advocates: There is power in numbers! If other NETWORK advocates from your district sign-up to participate, we will do our best to get you all connected. We also encourage you to think about who in your personal network you could invite to join you in your advocacy!

- Prepare your materials. In addition to the About NETWORK handout and NETWORK’s 2025 Legislative Priorities, you will also want to include a brief cover letter and make it clear that these materials are for the Representative and the District Director. In your letter, be sure to name that you’re a constituent and what town/neighborhood you live in, and include affiliations such as your parish or community, ministry or workplace, or where you volunteer.

- Prepare for your conversation. While this will most likely not be a long meeting, it’s important to think about what you will say. You will of course want to introduce yourself, NETWORK, and our 2025 Legislative Agenda; and if you’re going with a group, make sure that everyone briefly introduces themselves, and you can divide up what you are going to say. Remember: as this is a relationship-building meeting, it’s important to keep the tone friendly and respectful. This is not a time to debate policy. Also, please stick to the policies outlined on NETWORK’s 2025 Legislative Priorities; our Government Relations team has done the analysis, and we know that these are the first issues that the House is going to tackle through the budget reconciliation process. We also want to make sure that the staff understand who NETWORK is and what we work on.

This is also a time to gather important information about the office and your Representative. Here are some things you should learn during your visit:

- The names and emails of the District Director and Scheduler. This is key for scheduling future lobby visits!

- How you sign up for your Representative’s newsletter

- If your Representative is having any public events for constituents, such as town halls, virtual or in-person, in the next few months

- Be flexible during your visit. As this is not a formally scheduled lobby visit, you will most likely not know who you are going to meet when you go to the office. Since the House is on recess, you may actually get a few minutes to chat with your Representative. However, it’s more likely that you’ll speak with a District Director or someone in constituent services. Remember that not everyone in an in-district office deals with policy, so you may have to adjust how much you speak about NETWORK’s 2025 Legislative Agenda. Regardless of who you meet with, this is still an important first step to building a relationship with your Representative.

- Finishing touch and follow-up. If they’re available, be sure to get business cards for the District Director and Scheduler. Also, sign up for the Representative’s newsletter. And—just like you would for a lobby visit—a day or two after your visit, email the District Director and attach the About NETWORK and the 2025 Legislative Priorities documents to the email. If you met with them, of course thank them for their time. If you didn’t, simply let them know that you dropped by the office and that you’re looking forward to meeting with them in the future.

- Follow-up with NETWORK. As you know, we here at NETWORK love to see you in action. Please send us photos of you visiting the office, and, if it’s appropriate, include the person that you met with—especially if you do get a few moments with your Representative! About a week after January Recess, we will be sending out a report-back form so that we can collect information. Please take time to fill out the form!

Big corporations made $2.5 trillion in profits in 2021 alone, their most profitable year since 1950—and corporate food executives still raised prices.

Big corporations made $2.5 trillion in profits in 2021 alone, their most profitable year since 1950—and corporate food executives still raised prices.