We Must Repent From Christian Nationalism

Meg Olson

March 1, 2023

Readings for the Second Sunday of Lent:

Gn 12:1-4a

Ps 33:4-5, 18-19, 2, 22

2 Tm 1:8b-10

Mt: 17:1-9

God says to Abram in the First Reading this Sunday, “I will make of you a great nation.” Way too many people take those words to heart and twist them. For Christian nationalists, a great nation means a place that is made for and ruled by white Christians. As we saw in Charlottesville, on January 6, 2021, and elsewhere, this rule is meant to be a violent one. As Robert P. Jones’s research reveals, “White Americans who agree that ‘God intended America to be a promised land for European Christians’ are four times as likely as those who disagree with that statement to believe that ‘true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.’” And violence can be much more subtle than tiki torches, angry mobs overtaking the Capitol building, or vandalism at synagogues. Erasing Black history, banning books in school libraries, and denying gender-affirming care for transgender youth are all forms of violence. We must remain vigilant to these forms of violence, and, as God is described in the Psalm, “love justice and right.”

In the Gospel account of the Transfiguration, the disciples get a vision of who Jesus truly is and what awaits in the Kin-dom of God. But even then, they don’t fully comprehend, and they think and speak in worldly terms: “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here.” However, Jesus doesn’t need three tents, or even one. Humanity does—and it must hold all of us. As the recent Synod document instructs, “Enlarge the space of your tent.”

When Jesus tells the disciples to “Rise and do not be afraid,” he is speaking to all of us. We must trust in God and God’s creation and be neighbor and friend to all. However, we often don’t trust that God is there for us and will provide what we need. Even if we don’t resort to newsworthy violence, we twist the world into a frame in which we protect ourselves by dominating others. At NETWORK, we believe that transforming this dominative ethic by dismantling systemic racism is the beginning of building this country anew. But to do that, we must first educate ourselves on the pernicious reality of white supremacy, especially as it is found in our churches. We must enlarge the space of our tent and not be afraid to let God’s kin-dom in.

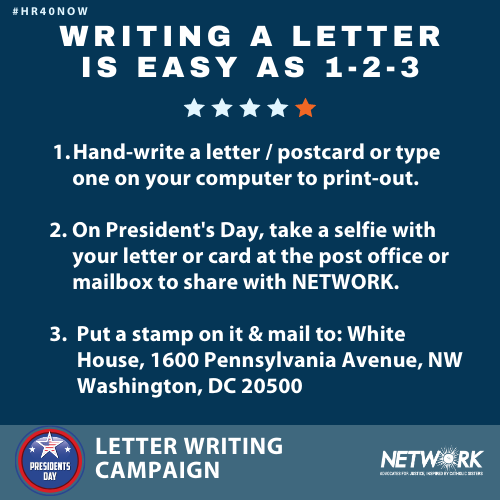

Take Action

Attend NETWORK’s Webinar: What to Expect from the 118th Congress

Join the webinar to see how the 118th Congress may impact NETWORK’s mission to build an inclusive, multiracial, and multi-faith democracy with better federal policy.

NETWORK’s Government Relations team will give their opinions on expectations for the 118th Congress. They will also share their hopes for NETWORK’s Build Anew policy priorities under the new Republican House Leadership.

Additional Resources

- Re-watch: White Supremacy and American Christianity

- Read the Baptist Joint Committee on Religious Liberty’s Report on Christian Nationalism and the January 6 Insurrection

- Return to Lent 2023